CORLEONE:

RECLAIMING ITS NAME FROM THE MAFIA

THE town of Corleone is Sicily is home to a fascinating and brave anti-Mafia resource centre which includes archive photographs and newspapers reports about the history of organised crime and a collection of legal documents used in landmark high-security ‘maxi-trial’ court cases during the 1980s.

The CIDMA centre in Corleone traces the roots of ‘banditry’ in Sicily and also documents the many struggles against organised crime by Sicilians through history.

The promotion of culture, progress and legality are central to the site’s aims. This includes rejecting Corleone’s negative portrayal as the ‘home of the Mafia’, which some campaigners feel has been partly created by films such as The Godfather and other popular culture about the Mafia. Instead, CIDMA encourages awareness and embracement of positive Sicilian identities, culture and history.

There are some similarities between the various community-based anti-Mafia centres and activists in Sicily and some other ‘post-conflict’ societies. Campaigners aim to promote fuller understandings of Sicily’s history and the uses of violence while also encouraging new non-criminal identities and pride in home towns and villages often dismissed as backward, unfashionable or criminal.

Located in hilly country south of Palermo, Corleone is a picturesque small town. But over the years its people, like the wider population, have suffered violence, murder, extortion, intimidation and political repression at the hands of the Mafia and its clients, which included wealthy land owners and powerful business people.

Overt violence and old fashioned protection rackets have lessened in recent years for a number of reasons including legal successes, increased resistance to the threat of blackmail and protection and the growth of modern technology which better-protects assets and monitors financial transactions, banking and money laundering. However the Mafia still operates and now uses more sophisticated and global methods to further its business interests.

But it remains important to understand the Mafia’s historical impact and remember it has not vanished – even if it has suffered some important setbacks.

Over the years, nobody was spared from the Mafia’s force – victims included police officers, lawyers, judges, peasants, shopkeepers, builders and trade union, political and community activists.

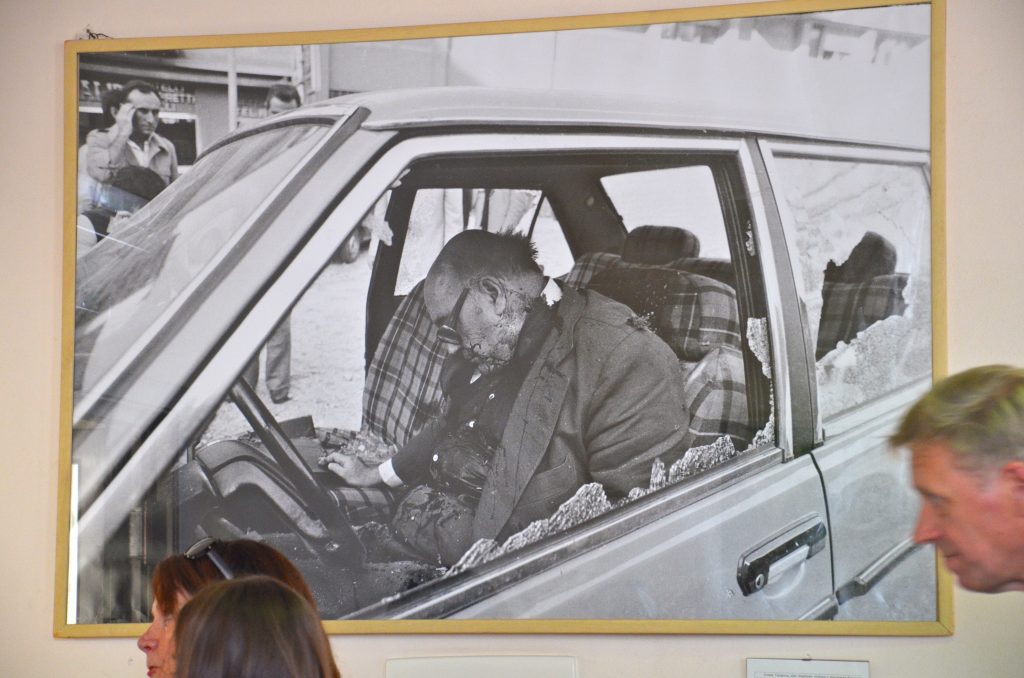

The entrance to the CIDMA centre has a mural dedicated to some of the high-profile victims of the Mafia in Corleone in the early 20th Century. Further inside are photographs of many more victims of Mafia killings across Sicily in the 1970s and 1980s. Multiple images showing the bodies of the dead and grief-stricken families, neighbours and communities.

Mafia intimidation of opponents and the general public was so strong and fear so widespread that some terrified relatives of the dead, such as mothers, fathers and children, sometimes attempted to disassociated themselves completely from the murder victim.

Acts of disassociation included symbolically turning chairs around so mourners would have their backs facing the deceased in the coffin. At least one case involved a family smashing the headstone of a new grave to publicly express their submission to the Mafia and the family’s apparent disapproval of the deceased’s behaviour which had led to their murder.

In the photo below, a young boy turns around to face the camera from a seat turned backward to the body of a victim, a man who was apparently shot through the mouth or had injuries to his mouth – probably for being perceived as an informer. Facial shootings were used as an extra punishment, hindering or preventing the traditional use of open coffins. Other killing rituals by the Mafia included the rearranging or removal of clothing or positioning of the body to reveal the victim’s religious tattoos or jewellery – designed to show that faith offered no protection from the Mafia.

Mafia violence reached a peak in the 1980s and early 1990s. Rival criminal families and groups fought for power in an especially murderous era with killings and counter-killings. Political and legal figures were also increasingly targeted because the Italian state and some political parties, especially the Italian Communist Party (PCI), attempted to stamp down on the Mafia.

Pio La Torre, a leader of the Communist Party and high-profile Sicilian radical who grew up in a poor farming family, introduced a new offence of Mafia conspiracy in Italian law and powers to confiscate assets. He was assassinated by the Mafia in 1982 in Palermo.

In 1986, a mass trial, known as the ‘maxi trial’, was held in Palermo, in a specially constructed underground maximum security courtroom. Almost 500 Mafia suspects were indicted with the majority subsequently found guilty of numerous crimes and then sentenced. The court case was long and complex and included an appeal, which dragged the proceedings into the early 1990s. Nonetheless, it was a major breakthrough against the Mafia.

Magistrates in the maxi-trial had worked as a wide group to make them less vulnerable to Mafia assassinations. However, prosecuting magistrates Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino were both assassinated within months of each other in 1992. They has played key roles in Mafia investigations along with others across Sicily and Italy which had raised fundamental questions about relationships between establishment political parties, business and organised crime. Palermo Airport was renamed in their memory and CIDMA uses a photograph of the pair on its signs and banners, as pictured below.

In the centre of Corleone is a small memorial statue to Placido Rizzotto. He was a local trade union activist murdered by the Mafia in the 1940s. Previously a socialist partisan who fought against Fascism during Mussolini’s reign, Rizzotto was kidnapped and murdered near Corleone in 1948. He had been campaigning for farmers rights to work on uncultivated land.

Rizzotto’s murder was witnessed by a young shepherd boy, Giuseppe Letizia, who was subsequently murdered the next day by a corrupt Mafia doctor using a lethal injection.

Reform of access to uncultivated land, the power of large country estates and better conditions for farmers were key political issues after the end of the Second World War. Sicily and southern mainland Italy were historically underdeveloped with widespread poverty and atrocious housing and working conditions.

It was not until the 1960s that Mafia leader Luciano Leggio eventually faced criminal proceedings for the murder of Rizzotto in 1948. However, Leggio was acquitted twice based on claims of insufficient evidence.

Decades later in 2009, the remains of Placido Rizzotto were discovered in rocky, remote terrain. Three years later the remains were identified using DNA comparisons taken from the exhumed body of his father. A formal state funeral in his honour was held in 2012 attended by Italian president Giorgio Napolitano. The statue is pictured above.