BLOG UNDERGOING CHANGES

FROM SCOTLAND TO ENGLAND, STEEL’S LEGACY ON FAMILIES, REGIONS & DEVOLUTION

The Redcar blast furnace demolition in November 2022 was a poignant event for the Teesside area of north-east of England. It symbolised very different eras over the past 40 years or so and topics which shaped families, regions, English and Scottish politics and devolution.

The Redcar blast furnace began operating in 1979 after years of steel industry development and investment on Teesside during the 1970s. But, in turn, some other UK steel-making centres, including in Scotland, were cut back or closed. This was the backdrop and experience of my family and others.

By coincidence the Redcar furnace was demolished in 2022 on the same day – in fact, within the same hour – that the London Supreme Court ruled the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh must have permission from the UK Westminster government before holding another Scottish independence referendum.

That decision, plus other factors, appears to have influenced Nicola Sturgeon’s resignation as Scotland’s First Minister.

The two events of November 23, 2023, both historic in different ways, were the climaxes of two separate processes. But they have some common ground in that they illustrate the policies, decisions, impacts and reactions to different Westminster governments over decades.

De-industrialisation in England and Scotland led to different political consequences and events. Scottish nationalism was fuelled by de-industrlalisation. In England, debates arose about the north-south divide, regional development, levelling-up etc but no northern political party has yet emerged to break the dominance of Labour or Conservatives. Although there are new smaller regional parties,

SCOTLAND AND ENGLAND

Teesside has a community with Scottish roots which includes families linked to the steel industry. Many of these moved to the area in the early 1970s. Back then, it perhaps never identified or described itself as a distinct community. British identity was probably dominant. Nonetheless, the Scottish community had experienced specific events including the running-down of Scottish steel making and industry (with more to follow) and the move to England. ‘Flitting’ was one word we used for moving – but ‘flitting’ in Scotland was associated with moving on the quiet, at night, at low profile. Maybe at night time. ‘Flitting’ we were told was done by people who were maybe in trouble, embarrassed, disgraced or similar.

Nowadays, in hindsight and with modern terms, we might describe that move from Scotland to England in other ways. Migration? Emigration? Freedom of movement? Economic pressure?

These contrasting events and decisions have shaped, and continue to shape, families, regions, politics and devolution debates in England and Scotland now.

add redcar blast furnace info here

CONSERVATIVES ON TEESSIDE

Rishi Sunak and Boris Johnson have visited Teesside many times to meet the current Conservative Tees Valley Mayor Ben Houchen. (Rishi Sunak’s parliamentary constituency borders a number of Teesside constituencies. Many of his constituents work on Teesside despite the seat being called Richmondshire). Freeports and devolution deals are flagship Conservative ideas and the Redcar blast furnace site’s regeneration is part of a number of projects on Teesside linked to these policies.

Previously, Margaret Thatcher visited Teesside on a number of occasions including her ‘walk in the wilderness’ photo-opportunity at the former Head Wrightson engineering site in Thornaby. Her era saw the creation of the Teesside Development Corporation. That included large regeneration and infrastructure schemes, such as the Tees Barrage.

Although much has been said about ‘red wall’ seats in England switching from Labour to Conservative in recent years, the political landscape of Teesside has, arguably, been more diverse for longer.

At an event in Middlesbrough last year, called Tees Politics History & Ideas, a Teesside University student recalled Conservative successes for Stockton South with MP Dari Taylor, The seat today is held by Matt Vickers, a former Teesside University law and business graduate, and other seats.

The former Langbaurgh seat over the years was held by Conservative and Labour MPs – Richard Holt, Ashok Kumar and Michael Bates. Ashok Kumar, an Asian MP, was connected to the steel industry. The seat was previously Cleveland and Whitby. Now, the two parliamentary seats in the Redcar vicinity are Redcar and Middlesbrough South & East Cleveland with Tory MPs Jacob Young and Simon Clarke. Middlesbrough and Stockton North still have Labour MPs, Andy McDonald and Alex Cunningham. Meanwhile Jill Mortimer is MP for Hartlepool. She has a farm in Knayton, North Yorkshire, a few miles south of Teesside, and studied law at Teesside University.

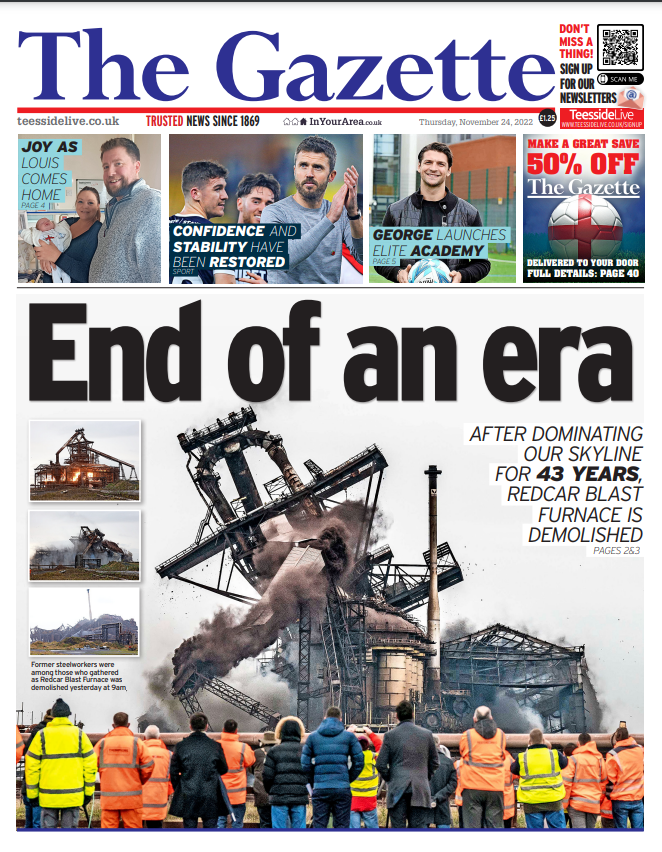

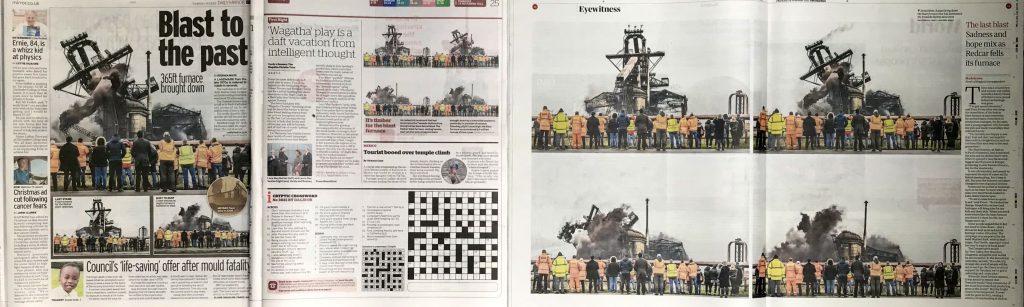

Below: Local and national newspaper reports of the demolition of Redcar blast furnace. Pictured from the top, Evening Gazette (Middlesbrough) The Times, Daily Telegraph, The Sun, Morning Star, Daily Mirror, the i (Independent) and The Guardian.

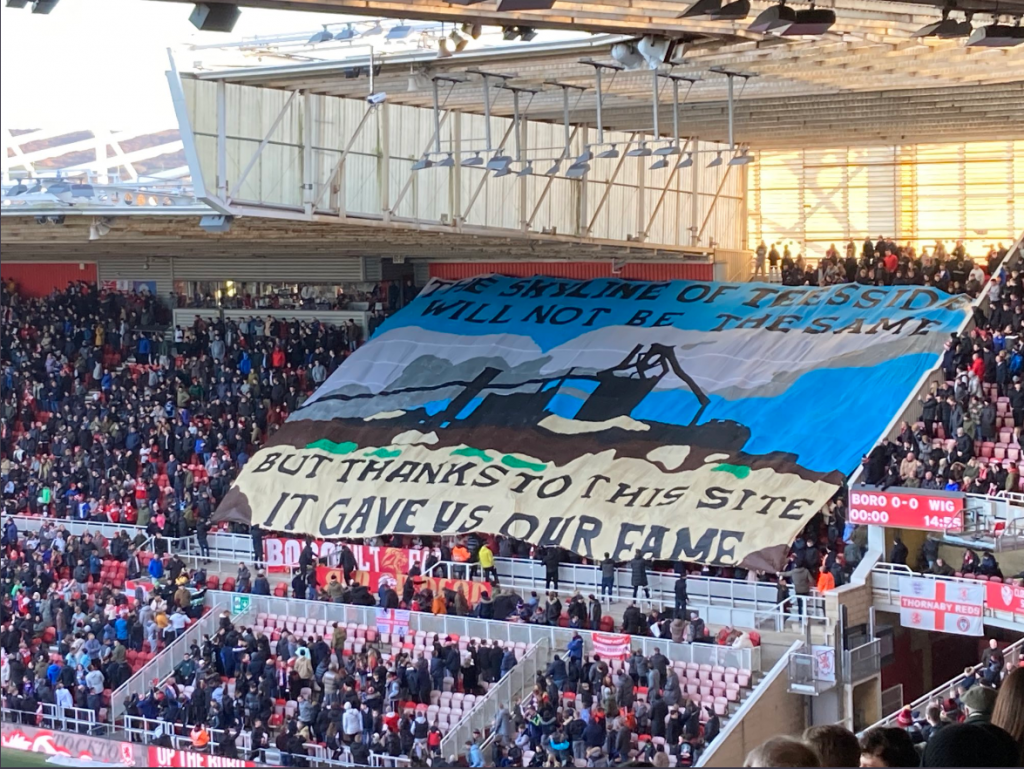

Below: Middlesbrough Football Club supporters in the Red Faction group display a banner portraying Redcar blast furnace at a home match in the Riverside Stadium, November 2022.

Redcar Blast Furnace, opened in 1979 and once among the biggest in Europe, was demolished on Wednesday, November 23, 2022. Explosives went off at 9am and in a few seconds the giant furnace collapsed to the ground. The sound of the explosion was heard for miles.

The demolition of such a symbolic industrial structure prompted a range of emotions and opinions, and varied levels of news coverage across local and national English and UK media.

Families, communities and regions which are most-closely associated with steel may perhaps be more conscious of these developments. But I think they are relevant to a wider audience and society at large because they feed into life and politics up to the present day.

TEESSIDE AND REDCAR STEEL – A VERY BRIEF HISTORY

Iron and steel industries arose during the Victorian era on Teesside when iron ore was discovered under the Cleveland Hills and North York Moors. Industry sprung up along the River Tees and, as part of this, Middlesbrough was founded and grew rapidly. Steel and iron works spread eastward from Middlesbrough along the Tees towards the North Sea. Other industries arose too including engineering, ship building, bridge building, chemicals and ports. At Redcar, ironworks were developed around the Warrenby and Coatham area.

From the late 1800s to the 1960s, new phases of steelworks and blast furnaces were developed or bought by companies such as Bolckow, Vaughan & Co, Dorman Long, Bell Brothers and Redpath Brown & Co. Dorman Long built the Sydney Harbour Bridge in Australia and the Tyne Bridge in Newcastle. In 1967, Dorman Long was taken into the new British Steel Corporation.

The modern Redcar blast furnace site was developed in the 1970s. The furnace formally began operating in 1979. It was reportedly the second-largest blast furnace in Europe. It was ignited symbolically with a flame carried from an older blast furnace at Clay Lane, South Bank, according to reports at the time. Like Teesside’s version of the Olympic flame.

But 1979 also brought political change with the arrival of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government. The British Steel Corporation was privatised in 1988 and became a PLC. In 1999 it merged with a Dutch steel maker to form Corus Group. In 2007 Corus was bought by Tata Steel. In 2009, Corus mothballed the Redcar blast furnace site. In 2011, it was bought by SSI and officially reopened in 2012. However the Redcar blast furnace site stopped operating in 2015 and SSI later went into liquidation that year.

Other Teesside steelworks, such as Teesside Beam Mill at nearby Lackenby, and Skinningrove, further down the coast remain operating under different owners, the Jingye Group, using the British Steel name. The Lackenby mill specialises in long beams of steel used in construction while Skinningrove specialises in steel used for earth-moving vehicles, bulldozers, forklifts and crane equipment. The basic steel now comes from Scunthorpe furnaces.

While steel-making in blast furnaces has gone from Teesside and the industry has changed vastly, steel still forms part of the economy of Teesside. Many media reports give the impression that all the steel industry has gone from the Tees, which is not the case. The reality is more complicated – but there’s no dispute that change has been dramatic over the past few decades.

Some people had hoped parts of Redcar blast furnace could be saved for a museum. Others thought the whole vast site should be cleared for new activities. There was range of opinion and emotions, and this was reflected in my own family’s conversations too. My mum, to this day, says some parts of the blast furnace should have been kept for the future, as a visitor centre or museum.

This post is not about the rights and wrongs of demolition, although those debates are important.

Instead, I want to first highlight Redcar blast furnace’s development and importance in 1970s Britain, which impacted on Scotland’s steel industry and families such as mine, and later changes in England and Scotland.

Scottish steel closures arguably supported rising support for Scottish nationalism in the 1970s and 1980s and support for the Scottish National Party (SNP) in central Scotland. More recently, English steel closures and changes have shaped new regional politics in England, such as devolution deals, the rise of Teesside’s Conservative regional mayor and the new freeports.

The Tees Valley regional Mayor, Conservative Ben Houchen, is promoting the new Teesworks project at the Redcar blast furnace site and surrounding land and port facilities. Teesworks is described as the biggest industrial regeneration scheme in Britain.

People are following it with interest and mix responses. On the one hand, people want change and regeneration. But the scheme has allegedly coincided with mass deaths of crabs and other crustaceans. Some claim dredging of the Tees has stirred-up old polluted materials from industry which has harmed the sea life. Others claim an algal bloom is to blame. The controversy has involved regional and national government, Ben Houchen, the fishing industry, scientists and the public. And is is ongoing,

Ben Houchen was at the Redcar blast furnace demolition ceremony in November 2022 and is a key figure in northern politics, devolution arrangements and the Conservative Party nationally.

Very recently, he was suggested as a mayor candidate for the new North-East Devolution Deal covering Northumberland, Newcastle and other Tyneside boroughs, Sunderland and County Durham. However, he said his focus is on his home turf of Teesside – Redcar, Middlesbrough, Stockton, Darlington and Hartlepool.

FAMILY STEEL LINKS

Family connections and histories to Redcar and Teesside steel represent another rich seam to explore.

My family moved from the Motherwell area near Glasgow to Teesside in 1974, along with other Scottish families linked to steel. They settled in places including Redcar, Saltburn, Guisborough, Great Ayton and Northallerton.

Redcar blast furnace was part of major investments on Teesside in the 1970s, when the British Steel Corporation focused production on key regions. Scottish steel was set for reductions over time, which would later include the closure of the Ravenscraig steelworks at Motherwell, which was also a modern complex.

In Scotland as a boy in the early 1970s, I could see the huge Ravenscraig steelworks at Motherwell from my family’s home in Wishaw a few miles away. Like Redcar, the Ravenscraig steelworks dominated the skyline.

My dad, originally from Inverness in the Highlands, first joined the steel industry in Glasgow in the late 1950s. He was then moved to Motherwell in the mid-1960s, as its steelworks were upgraded with the Ravenscraig developments.

My mum was from Glasgow and she had worked as a technical drawer for the Beardmore steel and engineering firm. She is pictured, below, at work as a very young woman in the drawing office in 1955. She grew up in Parkhead, Glasgow, next-door to Celtic Football Club.

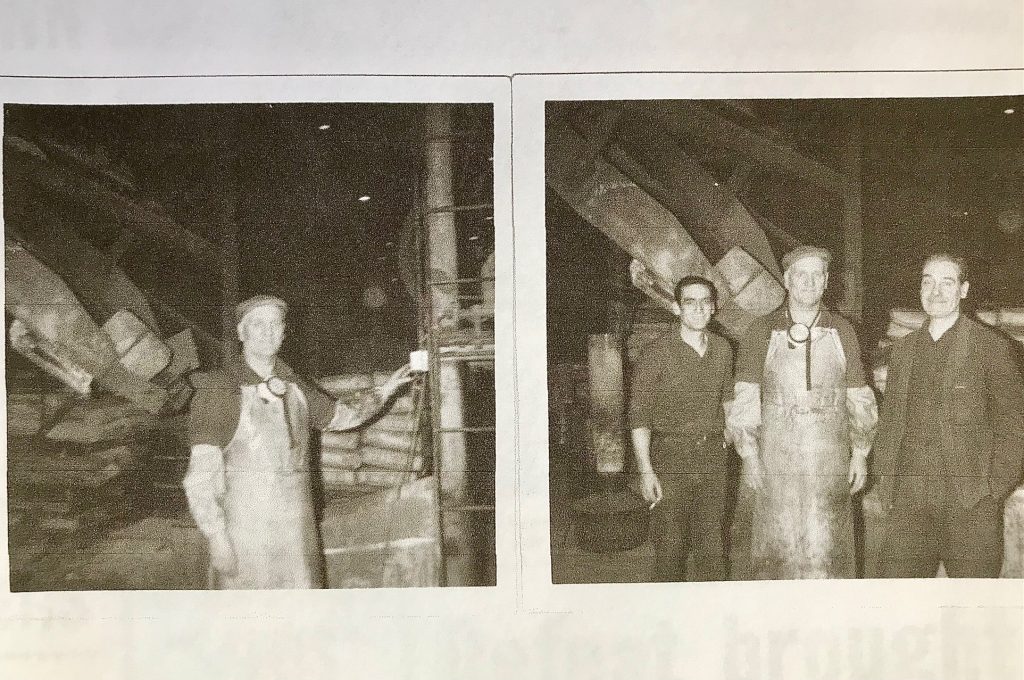

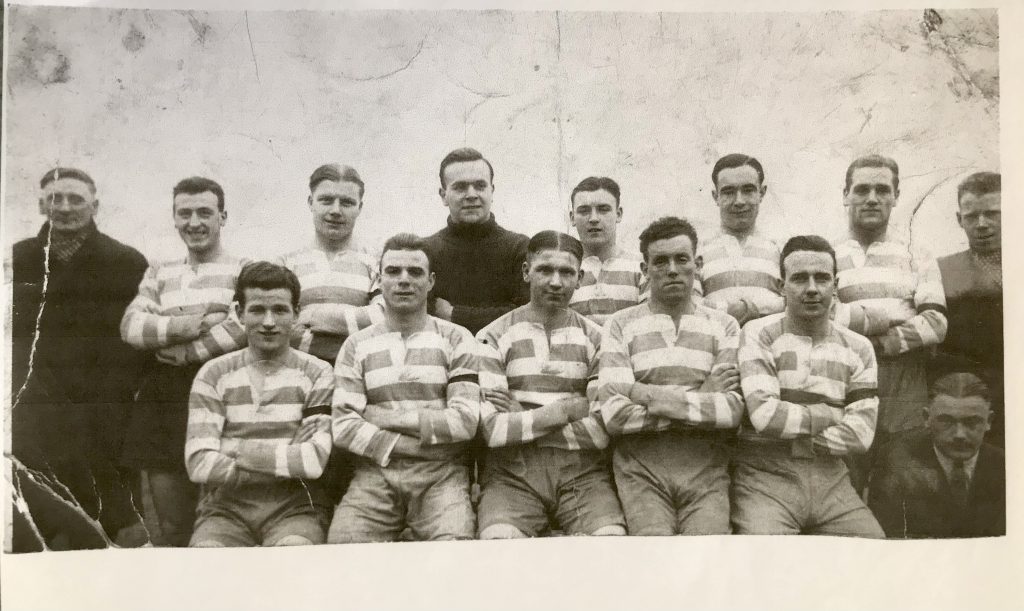

Her father and my grandfather, Matt Gibson, worked at Parkhead Forge for many years. He is also pictured here at the forge with workmates, perhaps in the 1950s or ’60s. Steel and engineering were central to Glasgow’s economy. Football was, and remains, central to Glasgow too. A lower photo shows him in a football team, probably Morton, who he played for as a young man, now called Greenock Morton.

CHANGING TIMES

Teesside in the 1970s saw other big developments too including the Ladgate Lane offices of British Steel in Middlesbrough and Steel House at Redcar, developed in 1977. ICI’s Wilton Centre was also built nearby in the same era. In many ways, the 1970s was a boom era. Middlesbrough and the wider Teesside region saw new industrial developments, new town centre developments, new shopping malls, new civic buildings, a new polytechnic (now Teesside University), new housing, new towns, new roads and new infrastructure.

Following government change in 1979, the whole UK steel industry, including on Teesside, saw dramatic job cuts and works closures in the 1980s and beyond.

At an event held in Middlesbrough’s MIMA museum last year, called ‘Tees Politics, History & Ideas’, an expert speaker talking about the Cleveland steel industry said a second blast furnace was due to be built at Redcar but it was never assembled after 1979. Apparently it lay in parts, unbuilt. I had no idea that a second blast furnace was planned.

My dad was among many who worked through these very different eras. In total, he spent six decades working in Scotland and England. His generation in particular witnessed a whole host of events and experiences, good and bad, from the post-war era onwards. Overall, he had a pretty good life but he had mixed emotions about the different eras and events.

In politics, he was not a Scottish nationalist. But he felt Scotland had suffered from some Westminster decisions and the demise of the Scottish steel industry saddened him. He was conservative with a small ‘c’ but became critical of Westminster Conservative governments in his later years. He became increasingly green but also felt Westminster governments were ineffective on many areas including modern industrial and regional development, especially for northern England.

He lived in the Teesside area for over 45 years. He was fond of the region, its wider countryside and coast, and its people.

In his retirement and later old age, I visited the Redcar blast furnace site and surrounding areas of Teesside with him a number of times. We were both interested in the mix of industry, river and coast, town and country, as is my mum.

I took my dad and mum to Redcar blast furnace, South Gare and Teesmouth in 2021, a few months before his death. His mind was always pretty sharp and his spirits were good, despite being physically frail. He enjoyed it. It was a cool, windy day by the Tees and the North Sea. But it was good to be there. I was really keen to take him to see the blast furnace and surrounding coastline for one last time.

From the Clyde to the Tees.

STEELWORKS IN CULTURE, MEDIA AND MEMORY

Redcar blast furnace has gone but it has been captured in photography, film, museum archives, music and culture.

Football supporters at Middlesbrough FC’s Riverside stadium recently unfurled a huge banner depicting the blast furnace with the message ‘The skyline of Teesside will not be the same. But thanks to the site it gave us our fame.’ Boro supporters in the Red Faction group were behind the banner, which was the latest in a long line of banners, flag displays and songs at Middlesbrough matches.

When Redcar steelworkers previously faced upheaval back in 2015, Middlesbrough fans famously held up a mass display of mobile phone torches to show their solidarity during an away at Manchester United’s Old Trafford stadium. It was visually stunning and emotionally moving.

In other activity, there are a number of exhibitions and archives including Steel Stories at Kirkleatham Museum and the British Steel Archive, which I understand is linked to Teesside University and Teesside Archives.

The photographer Ian MacDonald has had a number of books published about the blast furnace and other Teesside topics including Smith’s Dock shipyard. His work has appeared in books, newspapers and galleries.

I saw his Smith’s Dock work on location at Smith’s Dock in the 1980s when I was a photography student at Cleveland College of Art. I later interviewed him as a reporter for the Darlington & Stockton Times newspaper in the early 2000s.

His work is popular in Britain and internationally, especially in northern Europe. In the north-east of England and North Yorkshire, galleries including Whitby’s Reading Corner and MIMA in Middlesbrough sell his books. (Also as I write this in early 2023, The Guardian has coincidentally just published a feature about Ian MacDonald’s Middlesbrough photography.)

Cleveland’s other former blast furnaces have featured in media, music and culture too.

Folk singer Vin Garbutt was pictured near the old Clay Lane steelworks at South Bank for his Eston California LP in 1977 released by Topic Records. One of the songs on the album is Ring of Iron, about the old iron industries around Middlesbrough and the Cleveland Hills. The song was actually written by Graeme Miles, who wrote many songs about Teesside’s industry, coast and nearby moors in the 1950s and 1960s. The Teesside Fettlers released it on the Pye record label in 1967 and released other records later through the 1970s.

Rock singer Chris Rea released Steel River in the 1980s, offering his reflections on the area. I wasn’t the biggest fan of Chris Rea but I always liked Stainsby Girls, which was released in March 1985 and spent 12 weeks in the singles charts, and Driving Home For Christmas, which is probably better-known these days through being used on TV adverts.

In the 1990s. Redcar’s electronic-soul duo Tyrrel Corporation released a number of records including the single I’m Going Home’ which refers to Teesside’s industry and coast, and album, North East of Eden on the Cooltempo and Chrysalis labels.

Today, some people may say ‘good riddance’ to closed steelworks and get annoyed at what they may see as nostalgia. Patronising media stereotypes of redundant steelworkers and closed, rustbelt sites don’t reflect the complexity of such regions, then or now. Teesside and Clydeside continue to innovate, it could be argued.

Some may be saddened. Others may be hopeful about the future. Some may feel mixed emotions.

But for many people, Redcar blast furnace vanishing from our lives represented a poignant moment in time, whatever our politics or family background. I emphasised this in a letter to the Evening Gazette in Middlesbrough in the week of the demolition. I was really pleased the Gazette chose to publish the letter, shown below.

The Northern Echo also had extensive coverage including content by former editor Peter Barron, which was good to see. Peter’s father worked in the steel industry.